Nature Nanotechnology

http://www.nature.com/nnano/current_issue/rss/

Jia Wang

Abstract

Converting plastic waste into valuable products mitigates plastic pollution and lowers the carbon footprint of naphtha-derived aromatics. However, the difficulties of precisely controlling complex multiphase systems and the catalyst inefficiencies hinder process viability. Here we report a vapour-phase hydrogenolysis strategy catalysed by Ru single atoms on Co3O4 (RuSA/Co3O4), decoupling depolymerization from hydrogenolysis to overcome the toluene yield–selectivity trade-off. In a pressurized dual-stage fixed-bed reactor, polystyrene undergoes hydropyrolysis at 475 °C, followed by vapour-phase hydrogenolysis at 275 °C (0.4 MPa H2, 2.4 s), yielding toluene with 99% selectivity, 83.5 wt% yield and 1,320 mmol gcat.−1 h−1 rate. The RuSA/Co3O4 catalyst demonstrates excellent stability, maintaining >99% conversion and selectivity during 100 h continuous operation (turnover number 24,747), and effectively processes diverse real-world polystyrene wastes. Life-cycle assessment shows a 53% carbon footprint reduction over fossil-based methods, while techno-economic analysis estimates a competitive minimum selling price of US$0.61 kg−1, below the US$1 kg−1 industry benchmark.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Aromatic hydrocarbons such as benzene, toluene and xylenes (BTX), which underpin the production of chemicals and fuels1,2,3,4, are ~70% derived from fossil-based naphtha reforming and account for ~7% of global greenhouse gas emissions (Fig. 1a). Plastic manufacturing, another major source of carbon and resource pressure, is projected to exceed 1,100 Mt by 2050, further compounding global climate impacts5. Yet only 9% of plastic waste is currently recycled6,7. While mechanical recycling is viable for polyesters, it remains largely ineffective for polyolefins8,9,10,11. By contrast, chemical conversion of plastic waste into aromatics offers a route to reduce carbon emissions and fossil feedstock reliance, aligning with carbon neutrality targets12,13,14.

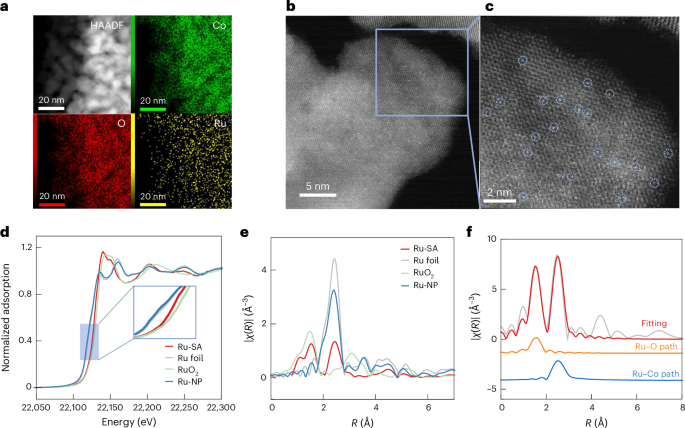

a, Petrochemical route for mixed aromatic hydrocarbon production. Conventional catalytic reforming process for toluene production from crude oil, operating at 450–500 °C and 1.5–3.5 MPa, yielding a mixture of aromatic compounds followed by extraction to obtain toluene. b, Selective vapour-phase catalytic upgrading of plastic waste into high-purity toluene. Comparison between previous approaches yielding diverse aromatic products and the selective hydrogenolysis strategy in this work.

Among the difficult-to-recycle plastic fractions, polystyrene (PS) has attracted particular interest for catalytic valorization into aromatics. Recent approaches target either functionalized aromatics via oxidative or photochemical methods, or bulk BTX compounds through hydrogenolysis or catalytic pyrolysis15,16,17,18. Notably, toluene stands out owing to its central role in the petrochemical industry, with global demand projected to rise from 37 Mt to 77 Mt by 203519. However, BTX-directed methods often result in broad product distributions and limited ability to tune selectivity, with toluene yields typically below 12 wt% and selectivity under 13% (refs. 20,21,22) (Fig. 1b). This limitation arises from the complexity of multiphase (gas–solid–liquid) reaction environments, where a thermodynamic mismatch between depolymerization and hydrogenation hampers selective C–C bond cleavage23,24,25. A representative case is hydrogenolysis in high-pressure autoclaves, where pressure–temperature feedback destabilizes the reaction environment. Beyond process-related constraints, catalyst design also plays a critical role in product selectivity. Zeolite catalysts (for example, Zeolite Socony Mobil, ZSM-5) are widely used in catalytic pyrolysis of plastic waste but typically generate C6–C13 aromatics with mixed monocyclic and polycyclic structures26,27,28,29 (Fig. 1b). Advances in process control and catalytic material engineering are essential for selective and efficient plastic waste valorization.

Here we report a tandem catalytic strategy combining hydropyrolysis and vapour-phase hydrogenolysis to selectively convert PS waste into toluene. The first stage thermally depolymerizes PS into aromatic intermediates, followed by gas-phase hydrogenolysis that directs C–C bond cleavage and enhances toluene selectivity over a solid catalyst. This tandem design adopts a gas–solid configuration that decouples depolymerization from hydrogenolysis, enhancing reaction control and scalability (Fig. 1b). To boost toluene selectivity, we developed a Ru single-atom catalyst on Co3O4, whose atom-level control affords high activity and selectivity30,31,32,33,34,35,36. In particular, RuSA/Co3O4 was designed to selectively cleave C–C bonds in key intermediates, steering the reaction towards the formation of toluene. Under reaction conditions of 0.4 MPa and 275 °C in the second-stage hydrogenolysis reactor, the RuSA/Co3O4 demonstrated a toluene selectivity of 99%, with a yield of 83.5 wt% and a formation rate of 1,320 mmol gcat.−1 h−1. Such selectivity streamlines product separation and improves energy efficiency, facilitating scalable plastic waste valorization.

Catalyst design and characterization

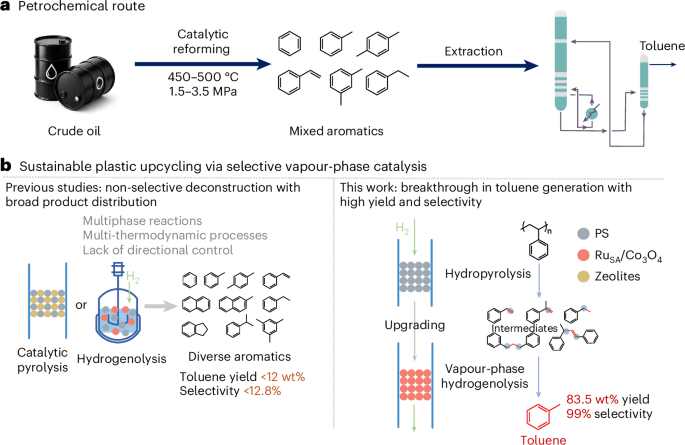

The RuSA/Co3O4 catalyst was prepared via hydrothermal synthesis of a cobalt carbonate precursor, followed by impregnation and calcination5,37,38,39. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (Fig. 2a) confirmed the uniform distribution of many small Co3O4 nanoparticles, approximately 20 nm in size. Scanning electron microscopy images showed that the synthesized Co3O4 exhibited a nanosheet morphology with sizes ranging from 500 nm to 1,000 nm (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Transmission electron microscopy images (Supplementary Fig. 1b,d) further revealed a lattice spacing of 0.467 nm, corresponding to the (111) plane of Co3O4. In addition, a weak peak at 284.2 eV in the electron energy loss spectrum was ascribed to the M4 edge of Ru (Supplementary Fig. 2), while a second peak at 543.5 eV corresponded to the O K-edge. These findings confirm the successful incorporation of Ru atoms into the Co3O4 structure and suggest a strong interaction between Ru and oxygen species. Ru nanoparticles on Co3O4 (RuNP/Co3O4) were prepared as a control, exhibiting structure and dispersion comparable to the single-atom catalyst (Supplementary Fig. 3).

a, Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy mapping images of RuSA/Co3O4 (green represent Co element, red represent O, and yellow represent Ru element). b, Atomic-scale structure of RuSA/Co3O4. High-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) scanning transmission electron microscopy image of RuSA/Co3O4. c, Enlarged region in b with blue circles marking the locations of Ru atoms. d, Normalized XANES spectra of the Ru K-edge. e, R-space extended X-ray absorption fine structure spectra of RuSA/Co3O4 and reference materials. f, Extended X-ray absorption fine structure fitting results for RuSA/Co3O4. Inset depicting the model used for fitting with two coordination shells.

X-ray diffraction analysis confirmed that the Co3O4 phase (powder diffraction file no. 43-1003) remained unchanged with either Ru single atoms or nanoparticles as active sites (Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5 and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). High-resolution transmission electron microscopy was used to further examine the microstructure. Aberration-corrected high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy imaging (Fig. 2b) visualized the Ru single atoms, and slight rotation of the (111) plane during imaging enhanced the clarity of the Ru atom distribution. High-contrast spots, highlighted by blue circles in the magnified image (Fig. 2c), represent the single Ru atoms dispersed on the Co3O4 nanosheets. No evidence of Ru atom aggregation was observed, confirming successful dispersion.

We characterized the electronic structure of the RuSA/Co3O4 catalyst using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy to explore the interaction between RuSAs and the Co3O4 support. In the high-resolution Co 2p spectrum (Supplementary Fig. 6), an increase in binding energy for both the 2p3/2 and 2p1/2 peaks indicated charge transfer between Ru and Co, with Ru oxidizing some Co sites and increasing the Co3+ component40,41 (Supplementary Table 3). However, no notable differences in the electronic state of Co were observed between RuSAs and RuNPs. The high-resolution O 1s spectrum revealed that the single-atom Ru catalyst has a lower defect oxygen content compared with the support, resulting from its coordination with oxygen vacancies in Co3O4. By contrast, RuNPs increased surface oxygen defects, because their larger size alters interactions with the support. The Ru 3p spectrum revealed that the 3p1/2 peak for RuSAs appeared at 463.8 eV, higher than the typical 461 eV for Ru (0), confirming the oxidized state of Ru within the Co3O4 substrate.

We used X-ray absorption spectroscopy to examine the oxidation state of Ru, based on the absorption edge position (Fig. 2d). In the RuSAs catalyst, Ru exhibits a +3 oxidation state, while in RuNPs, it remains in a zero-oxidation state. The X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) spectra reveal that the white line peak and near-edge absorption reflect multiple scattering effects around the central Ru atoms. Comparable to Ru foil, the RuNPs exhibit a near-edge adsorption peak shape but with diminished intensity, a consequence of their smaller particle size and unsaturated coordination structure. By contrast, the RuSAs show a near-edge peak distinct from both Ru foil and RuO2, indicating a unique Ru coordination environment. XANES-derived insights were validated by FEFF9 simulations using a single-atom Ru model, which reproduced experimental near-edge features41 (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Partial density of states analysis attributes the higher-energy spectral feature to Ru–Co electronic interactions, underscoring the role of Ru–O–Co coordination in shaping the XANES response (Supplementary Fig. 7b).

A detailed analysis of the single-scattering signal in the extended X-ray absorption fine structure region, processed with K2-weighting, reveals coordination differences between RuSAs and the reference sample (Supplementary Fig. 8). In the high-K region (K > 8 Å−1), reduced peak intensity indicates long-range disorder in the Ru atomic arrangement, particularly in the third coordination shell, confirming the absence of Ru-based compound formation and aligning with the design of single-dispersed Ru sites. R-space transformation of the RuSAs spectrum shows two prominent peaks at approximately 1.5 Å and 2.4 Å (Fig. 2e). The first peak corresponds to Ru–O coordination, while the second is attributed to long-range Ru–Co interactions, with the Ru–Co distance exceeding that of typical Ru–Ru bonding. On the basis of R-space curve analysis and morphology characterization, we proposed a Ru/Co3O4 (111) model (Fig. 2f). Fitting this model to the R-space curves using IFEFFIT revealed a coordination number of approximately 5-fold for Ru–O and 9-fold for the Ru–Co second coordination shell, suggesting the presence of Co vacancies in the support (Supplementary Table 4). Wavelet transform analysis (Supplementary Fig. 9), integrating both K-space and R-space data, further supports the proposed structure and curve interpretation.

Vapour-phase hydrogenolysis of model compounds

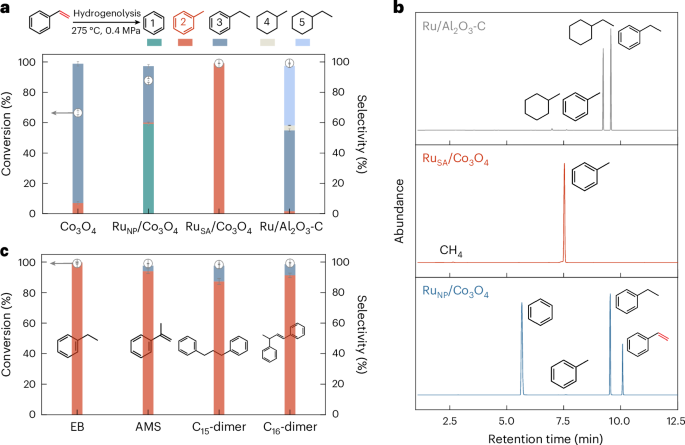

We investigated the selective vapour-phase hydrogenolysis of styrene, the monomer of PS, to produce toluene using various catalysts. The experiments were conducted in a pressurized dual-stage fixed-bed reactor, where styrene was vaporized in the first stage and subjected to hydrogenolysis in the second stage at 275 °C and 0.4 MPa (Supplementary Figs. 10–12). Among all catalysts investigated, Co3O4 achieved a 66.4% conversion of styrene, with ethylbenzene as the major product and only 7.2% toluene (Fig. 3a). This result indicates that Co3O4 can promote the hydrogenation of the vinyl group (–CH=CH2) in styrene to form ethylbenzene, but has poor activity to cleave the Csp3–Csp3 bond in ethylbenzene to produce toluene.

a, Conversion and selectivity profiles for styrene hydrogenolysis over different catalysts. b, Total ion chromatograms of products obtained from hydrogenolysis of styrene over different catalysts. c, Vapour-phase hydrogenolysis performance on additional PS-derived substrates over RuSA/Co3O4 catalyst. Selectivity values represent the distribution of aromatic hydrocarbon products and exclude gaseous by-products such as methane. The vapour-phase hydrogenolysis was conducted at 275 °C and 0.4 MPa. Catalyst loading was 30 mg, with a catalyst-to-feedstock mass ratio of 10:1. Each data point represents the mean of three independent experiments (n = 3), and error bars denote the standard deviation. EB and AMS denote ethylbenzene and α-methylstyrene, respectively.

Introducing Ru nanoparticles on Co3O4 (RuNP/Co3O4) substantially enhanced the catalytic performance, increasing styrene conversion to 87.9%. The main products were benzene and ethylbenzene, suggesting that RuNP/Co3O4 promote the cleavage of the Csp2–Csp3 bond between the benzene ring and the ethyl group in ethylbenzene. Remarkably, dispersing ruthenium as single atoms on Co3O4 (RuSA/Co3O4) led to complete conversion of styrene and a pronounced shift in selectivity. It gave an exceptional selectivity of toluene (>99%) among the aromatic hydrocarbons, demonstrating its high efficiency in transforming the vinyl group of styrene into a methyl group. Chromatograms in Fig. 3b show only a single toluene peak with RuSA/Co3O4, indicating that no other aromatic by-products were detected. This contrasts with other catalysts, which produce multiple peaks corresponding to diverse products such as benzene and ethylbenzene. For comparison, a commercial 5 wt% Ru/Al2O3 catalyst also achieved complete styrene conversion, with its catalytic activity contributing notably to hydrogenation of the aromatic ring, resulting in the formation of ethylbenzene and ethylcyclohexane as major products (Fig. 3a).

The selective hydrogenolysis of RuSA/Co3O4 was further evaluated using additional common products from PS depolymerization, including ethylbenzene, methylstyrene and C15/C16 dimers, besides styrene. As shown in Fig. 3c, near-complete conversion of each substrate was achieved, with toluene as the primary product and ethylbenzene as the only minor aromatic by-product. These results underscore the efficiency of RuSA/Co3O4 in facilitating selective Csp3–Csp3 bond cleavage between the benzyl group and the alkyl side chains, highlighting its potential for converting PS into toluene.

Tandem depolymerization and hydrogenolysis of PS waste

We further examined the tandem conversion of PS (weight-average molecular weight, Mw = 192 kDa; Supplementary Figs. 13–15 and Supplementary Table 5) to toluene in the same reactor. Hydropyrolysis of PS generated unstable aromatic intermediates (for example, styrene and its dimers), which were stabilized via online vapour-phase hydrogenolysis to selectively produce toluene. This integrated gas–solid process eliminates energy-intensive condensation and reheating steps required in conventional pyrolysis–hydrogenation schemes (Supplementary Fig. 16a), thereby improving energy efficiency and lowering carbon emissions. Enhanced mass transfer and precise reaction control enable better product selectivity, while avoiding multiphase (gas–liquid–solid) complications improves scalability and tunability compared with traditional systems (Supplementary Fig. 16b).

Optimization with RuSA/Co3O4 identified key parameters affecting toluene yield and selectivity. Increasing the first-stage hydropyrolysis temperature from 425 °C to 475 °C raised the yield from 56.3 wt% to a peak of 83.5 wt% (Supplementary Fig. 17), with no further improvement at higher temperatures. In the second-stage hydrogenolysis reactor, 200 °C yielded only 40.5 wt% toluene with by-products such as ethylbenzene and ethylcyclohexane (Supplementary Figs. 18 and 19), while 275 °C gave the highest yield. At 350 °C, excessive cracking led to 97.3 wt% methane (Supplementary Figs. 20 and 21). Elevated pressure (1.0 MPa) suppressed toluene formation and favoured cycloalkanes such as methylcyclohexane (90% selectivity; Supplementary Figs. 22–24). Notably, methylcyclohexane serves as both a hydrogen carrier and high-density aviation fuel, underscoring the versatility of this waste-to-value strategy.

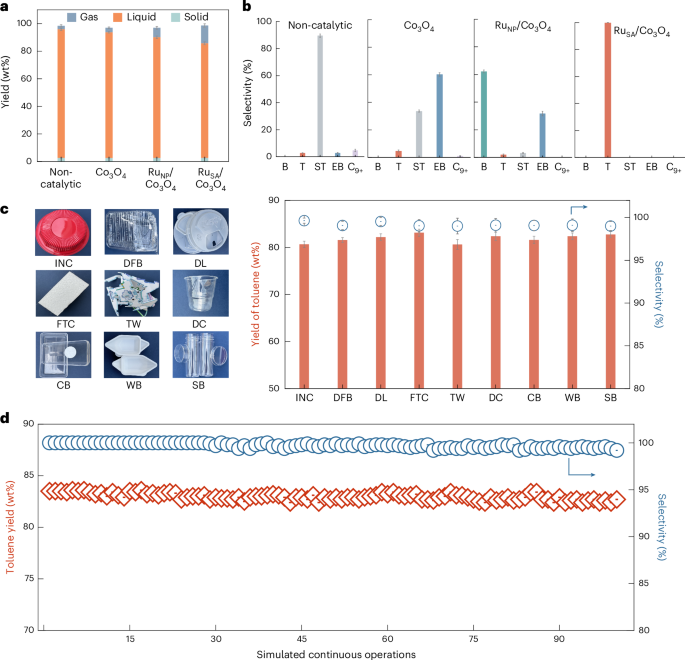

At 475 °C hydropyrolysis, 275 °C vapour-phase hydrogenolysis and 0.4 MPa H2, PS conversion yielded gas, liquid and solid products (Fig. 4a), with liquid products dominating. Without a catalyst, styrene was the main product (89.7% selectivity), along with toluene (2.7%), ethylbenzene, methylstyrene and C15–C16 aromatics (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 25). Co3O4 primarily produced ethylbenzene (60.3%) via vinyl hydrogenation, while RuNP/Co3O4 favoured benzene (62.3%) and ethylbenzene (31.7%). By contrast, RuSA/Co3O4 achieved near-exclusive toluene selectivity (83.5 wt%). Scale-up tests with liquid-phase product collection gave comparable yields (82.9 wt%), confirming catalytic robustness (Supplementary Figs. 26 and 27). The high specificity arises from selective cleavage of Csp3–Csp3 bonds in the vinyl group while preserving Csp2–Csp3 bonds. Time-resolved analysis further revealed product evolution dynamics (Supplementary Figs. 28 and 29).

a, Product distribution across gas, liquid and solid phases in non-catalytic and catalytic processes at a hydropyrolysis temperature of 475 °C, a hydrogenolysis temperature of 275 °C and a reaction pressure of 0.4 MPa. Each reaction used 30 mg of catalyst with a catalyst-to-PS mass ratio of 10:1. The H2 flow rate was set at 100 ml min−1, corresponding to a reaction time of 2.4 s under standard conditions. b, Product distribution from PS depolymerization. Selectivity towards benzene (B), toluene (T), styrene (ST), ethylbenzene (EB) and C9+ products across different catalysts. c, Scalability testing with post-consumer single-use PS wastes, including an instant noodle container (INC), disposable food box (DFB), drink lid (DL), foam takeout container (FTC), toy waste (TW), disposable cup (DC), cake box (CB), weighing boat (WB) and sample bottle (SB). d, Stability of RuSA/Co3O4 under simulated continuous PS feed. Each data point represents the mean of three independent experiments (n = 3), and error bars denote the standard deviation.

The performance of RuSA/Co3O4 was compared with that of ZSM-5, a widely used catalyst in the catalytic pyrolysis of plastics for producing aromatic hydrocarbons11,42. ZSM-5 yielded aromatic compounds with carbon chain lengths ranging from C6 to C12; however, it generated only 1.4% toluene while producing 12.2% polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons43 (Supplementary Fig. 30). The wide product distribution underscores the challenges of conventional aromatization pathways in directing selectivity towards toluene. We also evaluated our results against previous studies on PS hydrogenolysis. Under RuSA/Co3O4 catalysis at 0.4 MPa, with a calculated reaction time of 2.4 s, our process achieved an 8.4-fold increase in yield (83.5 wt% versus 11.9 wt%) and a 7.8-fold improvement in selectivity (99.9% versus 12.8%) compared with the best-reported values obtained under more stringent conditions44 (1 MPa for 6 h; Supplementary Tables 6–8).

RuSA/Co3O4 demonstrated scalability across 9 post-consumer single-use PS wastes (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Figs. 31 and 32), yielding ~81 wt% toluene with >99% selectivity and 1,320 mmol gcat.−1 h−1 formation rate. The instant noodle container sample yielded comparable toluene selectivity despite red dye, suggesting negligible interference likely owing to dye decomposition at 475 °C hydropyrolysis and 275 °C hydrogenolysis. For nitrogen-containing acrylonitrile styrene, RuSA/Co3O4 enabled 92.7% toluene selectivity while eliminating toxic by-products such as acrylonitrile (Supplementary Figs. 33 and 34). The system also tolerated halogen-containing PS wastes (expanded polystyrene (EPS), extruded polystyrene (XPS) and mixtures), consistently delivering ~80 wt% liquid yield and >97% toluene selectivity (Supplementary Fig. 35). Notably, real-world mixed PS waste maintained >99% toluene selectivity (Supplementary Fig. 36), highlighting the feedstock flexibility and robustness of this strategy.

To assess the durability and scalability of RuSA/Co3O4, we performed continuous vapour-phase hydrogenolysis using ethylbenzene, a representative PS-derived intermediate less prone to polymerization than styrene. In a fixed-bed reactor (275 °C, 0.4 MPa H2, weight hourly space velocity = 2.6 h−1), the catalyst maintained >99.9% conversion and >99% toluene selectivity for 100 h (Supplementary Fig. 38), achieving a high turnover number (TON) of 24,747. However, the low melting points of plastics hinder continuous solid feeding, as radiant heating in fixed-bed systems often causes premature softening and feeder blockage. Consequently, most studies assess catalyst stability via regeneration cycles rather than continuous polymer feeding28,44 (Supplementary Table 9). To address this challenge and emulate practical operations, we adopted an intermittent feeding strategy: PS was periodically introduced into a first-stage reactor, while the RuSA/Co3O4 catalyst remained stationary in the second-stage fixed-bed reactor for vapour-phase hydrogenolysis. The catalyst consistently delivered an 83 wt% yield of toluene with >99% selectivity across 100 feed cycles (Fig. 4d), indicating long-term stability and compatibility with real plastic waste. Raman and thermogravimetric analyses (TGA) analyses revealed negligible coking, and structural characterizations confirmed the intact Ru single-atom configuration (Supplementary Figs. 39–41).

Reaction mechanism and sustainability evaluation

To rationalize the mechanistic origin of the high styrene conversion and toluene selectivity observed over RuSA/Co3O4, we conducted density functional theory (DFT) calculations. The catalytic performance was found to be closely tied to the electronic properties of Ru species. Compared with Ru nanoparticles, Ru single atoms on Co3O4 exhibit a notably upshifted d-band centre (–1.3 eV versus –1.9 eV), as revealed by d-band centre theory and Fermi-level analysis (Supplementary Figs. 42–44). Hybridization among Ru 4d, Co 3d and O 2p orbitals in RuSA/Co3O4 suggests that coordination influences the electronic environment around active Ru sites, resulting in distinct adsorption behaviours compared with RuNP/Co3O4. The electron density difference revealed positive formal charges between Ru and its coordinated Co atoms, indicating a tendency for electron transfer from Ru to Co. This electron migration enhances the activity by facilitating the adsorption and activation of reactants on the active sites.

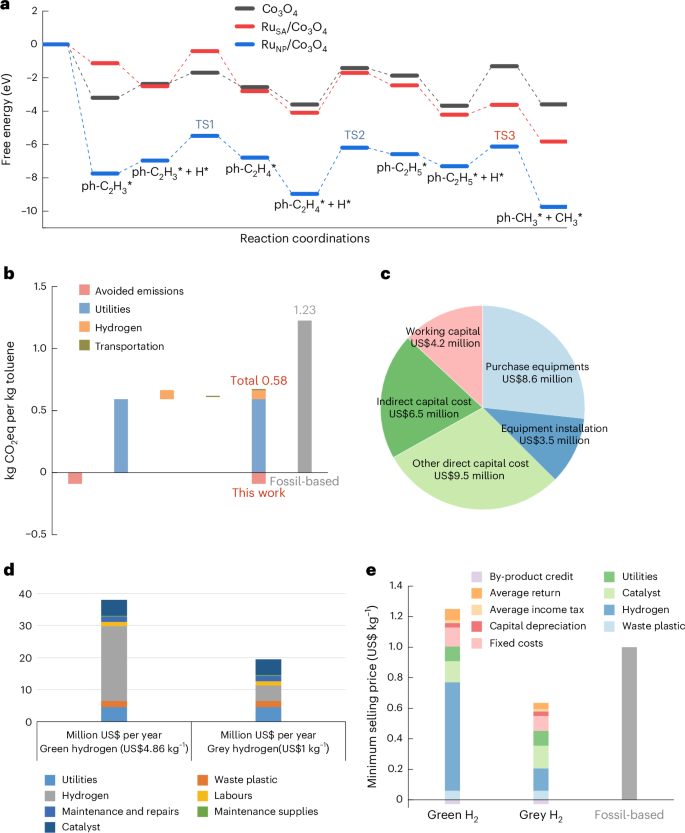

We evaluated the Gibbs free energies for four transition states involved in styrene hydrogenolysis. RuSA/Co3O4 exhibits a lower energy barrier of 2.38 eV in the hydrogenation of the vinyl group in styrene (ph-C2H4* + H*, TS2; Fig. 5a), compared with 2.78 eV for RuNP/Co3O4. This indicates that RuSA/Co3O4 has a lower energy barrier in the rate-determining step of vinyl group reduction. Following the hydrogenation of styrene to ethylbenzene, the adsorbed ph-C2H5* species at the catalyst interface undergoes C–C cleavage via hydrogenolysis to form toluene (Supplementary Fig. 44). The Co3O4 support exhibited a high energy barrier of 2.37 eV for ethylbenzene hydrogenolysis (ph-C2H5* + H* → ph-CH3* + CH3*, TS3). This barrier was reduced to 1.18 eV by RuNP/Co3O4 and further decreased to 0.59 eV with RuSA/Co3O4, highlighting the superior activity of single-atom Ru sites for this transformation (Supplementary Tables 10–12).

a, Free energy profiles of reaction pathways for key reaction steps on Co3O4, RuSA/Co3O4 and RuNP/Co3O4 catalysts. b, Life-cycle emissions for toluene production. Greenhouse gas emissions per kg of toluene produced, showing reductions achieved in this work compared with fossil-based methods. c, Capital cost distribution. Breakdown of capital investment for toluene production from PS, including contributions from working capital, equipment purchase, installation, indirect costs and other direct costs. d, Operating cost comparison. Annual operating costs for toluene production using green hydrogen (US$4.86 kg−1) and grey hydrogen (US$1 kg−1), detailing costs for utilities, hydrogen, waste plastic, catalyst and maintenance. e, Minimum selling price of toluene. Comparison of the minimum selling price of toluene produced with green hydrogen, grey hydrogen and fossil-based processes, considering costs and by-product credits.

To elucidate the superior toluene selectivity of single-atom Ru compared with Ru nanoparticles, we calculated the adsorption energies of toluene intermediates and their subsequent reactions with H* (Supplementary Fig. 45). The toluene intermediate exhibited stronger adsorption on Ru nanoparticles (−0.80 eV) than on single-atom Ru (−0.51 eV), suggesting that toluene adsorption is less favourable on the single-atom sites. In addition, we conducted a transition state energy barrier analysis for the hydrogenolysis of toluene to benzene. The energy barrier for the key transition state (ph-CH3* + H* → ph* + CH3*, TS4) was markedly lower on Ru nanoparticles (1.32 eV) than on single-atom Ru (3.32 eV), indicating that hydrogenolysis of toluene to benzene is less favourable on single-atom Ru compared with nanoparticles. Overall, Ru nanoparticles exhibit a lower energy barrier for toluene hydrogenolysis and a higher barrier for ethylbenzene hydrogenolysis, leading to the formation of a broader range of products during PS depolymerization and thus reducing toluene selectivity.

The life-cycle assessment (LCA) of the waste-to-toluene production evaluates the environmental footprint and sustainability of this circular transformation by quantifying cradle-to-gate emissions (Supplementary Fig. 46 and Supplementary Tables 13–16). This LCA focuses on the global warming potential (GWP) across a 100-year horizon, yielding a value of 0.58 kg CO2 equivalence (CO2-eq) per kg of toluene produced, a 53% reduction compared with the petroleum-based toluene benchmark of 1.23 kg CO2-eq per kg (Fig. 5b). Utilities were identified as the largest contributor to GWP among key process elements, highlighting the potential of renewable energy integration to improve environmental performance.

Alongside the LCA, a techno-economic analysis (TEA) was conducted to evaluate the feasibility of a dedicated facility in Shanghai, China, capable of processing the full accessible feedstock. Using a discounted cash flow model, the minimum viable selling price was determined (Supplementary Tables 17–19). Capital expenditure (CAPEX) was dominated by pyrolysis and hydrotreating units, with additional costs attributed to engineering and contingencies (Fig. 5c). Operating expenditure (OPEX) was driven by hydrogen under green pricing and by catalyst and utilities under grey pricing (Fig. 5d). Feedstock, labour and maintenance were also notable OPEX components.

Sensitivity analysis of the minimum selling price of plastic-derived toluene revealed strong dependence on hydrogen pricing: the minimum selling price increases to US$1.22 kg−1 with green hydrogen and decreases to US$0.61 kg−1 with grey hydrogen, both remaining competitive compared with the commercial toluene price of US$1 kg−1 (Fig. 5e, Supplementary Fig. 47 and Supplementary Tables 20–22). These scenarios highlight the economic advantage of plastic-derived toluene over fossil-based alternatives, reinforcing the economic feasibility of this sustainable pathway. Future efforts should prioritize hydrogen supply-chain optimization and process-level energy integration to realize scalable, circular plastic-to-toluene technologies.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates a highly selective vapour-phase strategy for converting PS waste into toluene using a Ru single-atom catalyst on Co3O4. The tandem hydropyrolysis–hydrogenolysis process achieves 83.5 wt% yield and >99% selectivity under mild conditions, enabled by atomically dispersed Ru that lowers energy barriers for C–C bond cleavage. The catalyst maintains structural integrity and performance over 100 h of continuous operation. Integrated life-cycle and techno-economic assessments support its environmental and economic viability. However, challenges remain in continuous solid-plastic feeding, energy integration and scalability beyond PS. Future work should address feedstock generality, long-term fouling resistance and system-level energy optimization to accelerate industrial translation.

Methods

Materials

Cobalt(II) nitrate hexahydrate (Co(NO3)2·6H2O, 98%), sodium carbonate (Na2CO3, 99%), polyvinyl pyrrolidone (PVP, 98%), ethanol, methanol and ethylene glycol (analytical grade) were purchased from China National Pharmaceutical Group or Beijing Tongguang Fine Chemical and used without further purification. Ruthenium precursors, including RuCl3·3H2O and Ru(NO)(NO3)3 (98%), were supplied by Alfa Aesar. PS (Mw = 192 kDa) and acrylonitrile styrene plastics were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Post-consumer PS wastes were collected from a recycling centre in Nanjing, China. External gas–chromatography (GC) standards (styrene, toluene, ethylbenzene, benzene and methylcyclohexane) were also purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Commercial ZSM-5 (Si/Al = 23, surface area = 425 m2 g−1) was obtained from Alfa Aesar.

Catalyst preparation

The Co3O4 precursor was synthesized by adding 12.5 ml of concentrated NH3·H2O (solution A) to 15 ml of ethylene glycol (solution B) under stirring. After 2 min, 3.5 ml of 1 M Na2CO3 and 5 ml of 1 M Co(NO3)2 were sequentially introduced. The mixture, which gradually turned violet, was stirred for 20 min, transferred to a 50 ml Teflon-lined autoclave and heated at 170 °C for 17 h. The resulting solid was washed with deionized water and ethanol, and then dried at 60 °C.

To prepare Ru single-atom catalysts (RuSA/Co3O4), 200 mg of Co3O4 precursor and 4.88 mg of RuCl3·3H2O were dispersed in 20 ml of ethanol, sonicated for 5 min and stirred at 40 °C for 12 h. The solid was recovered by centrifugation, washed with ethanol, dried at 60 °C under vacuum and calcined in air at 300 °C for 2 h.

For Ru nanoparticle (RuNP) synthesis, 7 ml of Ru(NO)(NO3)3 solution (10 mg ml−1), 224 mg of PVP (Mw = 30,000) and 193 ml of ethylene glycol were stirred to form a homogeneous solution, which was then refluxed at 200 °C for 3 h in air. The product was collected by centrifugation, washed with ethanol and redispersed in 20 ml of ethanol.

To synthesize RuNP/Co3O4, 200 mg of Co3O4 precursor and 1 ml of the RuNP dispersion were mixed in 20 ml of ethanol, sonicated for 5 min and stirred at 40 °C for 12 h. After washing and drying, the sample was calcined in air at 300 °C for 2 h.

Catalyst characterization

X-ray powder diffraction was performed on a Rigaku RU-200b diffractometer using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy was conducted on an ULVAC PHI Quantera microscope to analyse surface composition. Transmission electron microscopy images were obtained with a Hitachi H-800 microscope to examine catalyst morphology. High-resolution transmission electron microscopy, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy line scans and mappings were captured using a JEOL JEM-2100F operating at 200 kV. High-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy was performed on a JEOL 200F microscope at 200 keV, equipped with a probe spherical aberration corrector. Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy was conducted using a Thermo Fisher iCAP PRO instrument.

X-ray absorption fine structure spectra at the Ru K-edge were collected at the 1W1B beamline of the Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility (BSRF), operating at 2.5 GeV with a current of 250 mA. Fluorescence-detected spectra were acquired using a 19-element high-purity Ge detector array, with Mo and Fe filters. For X-ray absorption fine structure measurements, 40 mg of RuSA/Co3O4 or RuNP/Co3O4 was ground and pressed into 8 mm pellets. Reacted catalysts mixed with quartz were prepared by grinding 60 mg of the sample for 10 min and pressing into 8 mm pellets. Reference data for Ru foil, RuO2 and RuCl3 were collected in transmission mode at both the 1W1B and BL14W1 beamlines.

Tandem fixed-bed reactor and online GC–MS analysis

A custom-designed two-stage pressurized fixed-bed reactor (RX3050TR, Frontier Lab) was used for the upcycling of PS waste. The set-up consists of two vertically connected stainless-steel reactors with inert coatings and independent temperature control. The first-stage reactor (76 × 125 × 75 mm, 100–900 °C) enables hydropyrolysis of up to 50 mg PS, which is loaded in a stainless-steel sample cup, introduced via a high-pressure solid sampler. The second-stage reactor (76 × 125 × 160 mm, 100–700 °C) contains a quartz tube (3 mm inner diameter, i.d.) packed with catalyst (30 ± 0.05 mg) diluted with SiO2 for vapour-phase hydrogenolysis. Both reactors have an inner diameter of 4.6 mm. Hydrogen was supplied at 100 ml min−1, and the catalyst-to-feedstock ratio was fixed at 10:1. The system pressure (0.1–3 MPa) was regulated via a high-pressure flow controller (HP-3050FC). Catalysts were pre-reduced at 300 °C for 2 h in H2 before each run.

Sample injection was conducted using either a manual high-pressure injector or an autosampler module capable of sequentially delivering up to 48 sealed samples without air exposure (Supplementary Figs. 13 and 14). In model experiments, styrene was vaporized at 275 °C in the first stage and hydrogenolysed at 275 °C and 0.4 MPa in the second stage. Catalyst stability was evaluated using 30 mg of RuSA/Co3O4 over 100 PS feeding cycles without catalyst replacement.

Product analysis was performed via an online GC–MS system equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD; Agilent 8890–5977B) equipped with a 50 m HP-PONA column (0.20 mm i.d., 0.50 μm film). The GC oven was programmed from 45 °C to 320 °C at 10 °C min−1. MS scans ranged from m/z 2 to 550, with product identification via the NIST library and external standards. Condensed liquid products were analysed offline using an Agilent 8890–7000D GC–MS with an HP-5MS column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm).

Scale-up validation and long-term catalyst stability

To assess the scalability and durability of RuSA/Co3O4, we conducted two scale-up experiments in fixed-bed reactors. In the first test, a standard single-stage fixed-bed reactor (1,300 × 600 × 1,000 mm; inner tube diameter 8 mm, height 430 mm) with dual-zone temperature control was loaded with 400 mg RuSA/Co3O4, diluted in quartz sand (total bed volume 2 ml). Ethylbenzene (1.2 ml h−1) was chosen as a surrogate feed to avoid styrene polymerization. After upstream vaporization, the feed entered the catalyst bed along with H2 (50 ml min−1) at 275 °C and 0.4 MPa. The reaction ran continuously for 100 h with a weight hourly space velocity (WHSV) of 2.6 h−1, and effluents were periodically analysed by GC–MS equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID).

In the second test, a laboratory-scale tandem reactor was used to evaluate liquid yields under realistic PS conversion conditions. Two stainless-steel tubular reactors (i.d. 8 mm) were connected in series. The first stage (400 mm, 475 °C) depolymerized 200 mg of PS per run, while the second stage (350 mm, 275 °C) carried out vapour-phase hydrogenolysis. Both operated at 0.4 MPa with 100 ml min−1 H2 flow. The catalyst-to-feed mass ratio was fixed at 10:1, with an estimated residence time of 38.2 s. Liquid products were trapped downstream using dichloromethane at –15 °C and analysed via GC–MS.

DFT calculations

Spin-polarized DFT calculations were carried out using the QUICKSTEP module in CP2K (v2024.2) with the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional and Goedecker–Teter–Hutter (GTH) pseudopotentials. A MOLOPT double-ζ valence polarized basis set and a 400 Ry plane-wave cut-off were used. Dispersion was corrected via Grimme D3 with Becke–Johnson damping. Geometry optimizations used Γ-point sampling and conventional self-consistent field (SCF) diagonalization. The Co3O4(111) surface was modelled using a 4-layer slab (44 atoms). DFT + U (effective Hubbard U parameter, Ueff = 5.9 eV for Co, 3.3 eV for Ru) was applied to account for d-electron correlation. Density of states and charge density differences were analysed using Multiwfn, with SCPA and Gaussian broadening for partial density of states (Supplementary Methods).

Process modelling and LCA

Process simulation was performed using Aspen Plus based on experimental elemental balances. The model includes heat recovery, PS hydropyrolysis and vapour-phase hydrotreating at 275 °C, producing toluene and methane. Utility demands were estimated assuming 70% electric heating efficiency, with overall plant energy consumption benchmarked against literature, conservatively assuming heating accounts for 74% of total energy use.

A cradle-to-gate LCA was conducted per ISO 14040, with 1 kg of toluene as the functional unit. System boundaries begin at the municipal waste centre, excluding upstream plastic emissions. Plastic transport was assumed to cover 100 km. The life-cycle inventory, including key assumptions, was derived from simulation outputs and literature sources (Supplementary Notes). Methane by-product utilization was modelled via system expansion, with avoided emissions estimated using GREET 2023. GWP over a 100-year horizon (GWP100) was used as the primary environmental indicator.

TEA

A TEA was conducted using Shanghai as a representative case to evaluate the economic feasibility of the proposed process. The model focused on plastic waste streams not suitable for material recycling and assumed a feedstock cost of US$0.05 kg−1, with PS accounting for 6% of total plastic waste. Transportation costs were excluded, while sorting costs were included.

Minimum selling prices of toluene were estimated using a discounted cash flow model incorporating capital (CAPEX) and operating (OPEX) expenditures. CAPEX was calculated using the six-tenth factor rule and adjusted via the chemical engineering plant cost index. A sensitivity analysis identified feedstock cost, hydrogen price and toluene yield as key drivers. Detailed assumptions, equipment costs and parameter breakdowns are provided in Supplementary Notes.

Data evaluation

The conversion of PS was calculated as follows:

where mbefore and mafter are the masses of the stainless-steel sample cup before and after reaction, respectively.

The yield of hydrocarbons (for example, aromatics and cycloalkanes) from the hydropyrolysis–hydrogenolysis of PS was calculated as follows:

Liquid products were quantified by external calibration using GC/MS. Calibration curves were established for each compound (≥99.9%, GC grade, Sigma-Aldrich) under identical analytical conditions. All curves showed excellent linearity (R2 > 0.995). Gaseous products were quantified component-by-component via GC with external standards.

Product selectivity from PS depolymerization was calculated as follows:

where mj represents the mass of a specific hydrocarbon product, such as benzene, toluene, styrene, ethylbenzene or C9+ aromatics, and ∑mj denotes the total mass of all liquid hydrocarbon products.

Toluene formation rate (mmol gcat.−1 h−1) was calculated as follows:

where mcatalyst denotes the mass of catalyst loaded, and the reaction time corresponds to the total residence time of reactants in the reactor, calculated as follows:

To ensure accurate residence time estimation, we assessed whether the tandem fixed-bed reactor operates under plug flow conditions by calculating the Péclet number (Pe) and comparing convective and diffusive timescales. A sufficiently high Pe, together with favourable dimensionless criteria, suggests near-ideal plug flow behaviour, characterized by negligible axial dispersion and effective radial mixing. Pe is defined as follows:

where u is the superficial gas velocity (m s−1), D is the characteristic length (m), ρ is the gas density (kg m⁻3), μ is the dynamic viscosity (Pa s) and DAB is the molecular diffusion coefficient (m2 s−1).

The TON was determined as the total moles of toluene produced per mole of Ru in the catalyst during continuous operation:

where nToluene is the total amount of toluene formed, and nRu is the number of moles of Ru in the catalyst.

Data availability

All data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

-

Stone, M. L. et al. Continuous hydrodeoxygenation of lignin to jet-range aromatic hydrocarbons. Joule 6, 2324–2337 (2022).

-

Hussain, I. et al. Chemical upcycling of waste plastics to high value-added products via pyrolysis: current trends, future perspectives, and techno-feasibility analysis. Chem. Rec. 23, e202200294 (2023).

-

Wu, Y. et al. Benzene, toluene, and xylene (BTX) production from catalytic fast pyrolysis of biomass: a review. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 11, 11700–11718 (2023).

-

Kasipandi, S. & Bae, J. W. Recent advances in direct synthesis of value-added aromatic chemicals from syngas by cascade reactions over bifunctional catalysts. Adv. Mater. 31, e1803390 (2019).

-

Zhang, Z. et al. Mixed plastics wastes upcycling with high-stability single-atom Ru catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 22836–22844 (2023).

-

Ellis, L. D. et al. Chemical and biological catalysis for plastics recycling and upcycling. Nat. Catal. 4, 539–556 (2021).

-

Jie, X. et al. Microwave-initiated catalytic deconstruction of plastic waste into hydrogen and high-value carbons. Nat. Catal. 3, 902–912 (2020).

-

Wu, X. et al. Polyethylene upgrading to liquid fuels boosted by atomic Ce promoters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 63, e202317594 (2024).

-

Kots, P. A., Vance, B. C., Quinn, C. M., Wang, C. & Vlachos, D. G. A two-stage strategy for upcycling chlorine-contaminated plastic waste. Nat. Sustain. 6, 1258–1267 (2023).

-

Conk, R. J. et al. Polyolefin waste to light olefins with ethylene and base-metal heterogeneous catalysts. Science 385, 1322–1327 (2024).

-

Duan, J. et al. Coking-resistant polyethylene upcycling modulated by zeolite micropore diffusion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 14269–14277 (2022).

-

Du, J. et al. Efficient solvent- and hydrogen-free upcycling of high-density polyethylene into separable cyclic hydrocarbons. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 772–779 (2023).

-

Xu, Z. et al. Chemical upcycling of polyethylene, polypropylene, and mixtures to high-value surfactants. Science 381, 666–671 (2023).

-

Li, H. et al. Hydroformylation of pyrolysis oils to aldehydes and alcohols from polyolefin waste. Science 381, 660–666 (2023).

-

Xu, Z. et al. Cascade degradation and upcycling of polystyrene waste to high-value chemicals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2203346119 (2022).

-

Zeng, G., Su, Y., Jiang, J. & Huang, Z. Nitrogenative degradation of polystyrene waste. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 2737–2746 (2025).

-

Martín, A. J., Mondelli, C., Jaydev, S. D. & Pérez-Ramírez, J. Catalytic processing of plastic waste on the rise. Chem 7, 1487–1533 (2021).

-

Liu, Y., Ma, B., Tian, J. & Zhao, C. Coupled conversion of polyethylene and carbon dioxide catalyzed by a zeolite-metal oxide system. Sci. Adv. 10, eadn0252 (2024).

-

Toluene Market Size, Growth, Analysis & Forecast, 2035 (ChemAnalyst, 2023); https://www.chemanalyst.com/industry-report/toluene-market-665

-

Zhang, F. et al. Polyethylene upcycling to long-chain alkylaromatics by tandem hydrogenolysis/aromatization. Science 370, 437–441 (2020).

-

Liu, S., Kots, P. A., Vance, B. C., Danielson, A. & Vlachos, D. G. Plastic waste to fuels by hydrocracking at mild conditions. Sci. Adv. 7, eabf8283 (2021).

-

Chu, M. et al. Layered double hydroxide derivatives for polyolefin upcycling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 10655–10665 (2024).

-

Wang, Y.-Y. et al. Catalytic hydrogenolysis of polyethylene under reactive separation. ACS Catal. 14, 2084–2094 (2024).

-

Vance, B. C., Najmi, S. & Vlachos, D. G. Polystyrene hydrogenolysis to high-quality lubricants using Ni/SiO2. ACS Catal. 14, 5389–5402 (2024).

-

Tang, M. et al. Upcycling of polyamide wastes to tertiary amines using Mo single atoms and Rh nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 64, e202416436 (2025).

-

Gao, L. et al. Selective upcycling of polyethylene over Ru/H-ZSM-5 bifunctional catalyst into high-quality liquid fuel at mild conditions. ChemSusChem 17, e202400598 (2024).

-

Fu, L. et al. Catalytic pyrolysis of waste polyethylene using combined CaO and Ga/ZSM-5 catalysts for high value-added aromatics production. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 10, 9612–9623 (2022).

-

Wei, J. et al. Hydrodeoxygenation of oxygen-containing aromatic plastic wastes to liquid organic hydrogen carriers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 62, e202310505 (2023).

-

Liu, J. et al. Ni/HZSM-5 catalysts for hydrodeoxygenation of polycarbonate plastic wastes into cycloalkanes for sustainable aviation fuels. Appl. Catal. B 338, 123050 (2023).

-

Ding, S., Hülsey, M. J., Pérez-Ramírez, J. & Yan, N. Transforming energy with single-atom catalysts. Joule 3, 2897–2929 (2019).

-

Li, R. et al. Polystyrene waste thermochemical hydrogenation to ethylbenzene by a N-bridged Co, Ni dual-atom catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 16218–16227 (2023).

-

Chen, Y. et al. Single-atom catalysts: synthetic strategies and electrochemical applications. Joule 2, 1242–1264 (2018).

-

Lee, K., Jing, Y., Wang, Y. & Yan, N. A unified view on catalytic conversion of biomass and waste plastics. Nat. Rev. Chem. 6, 635–652 (2022).

-

Xiong, H. et al. Engineering catalyst supports to stabilize PdOx two-dimensional rafts for water-tolerant methane oxidation. Nat. Catal. 4, 830–839 (2021).

-

Zhang, Z. et al. Charge-separated Pdδ−-Cuδ+ atom pairs promote CO2 reduction to C2. Nano Lett. 23, 2312–2320 (2023).

-

Hannagan, R. T., Giannakakis, G., Flytzani-Stephanopoulos, M. & Sykes, E. C. H. Single-atom alloy catalysis. Chem. Rev. 120, 12044–12088 (2020).

-

Wang, L. et al. The reformation of catalyst: from a trial-and-error synthesis to rational design. Nano Res. 17, 3261–3301 (2023).

-

Wang, Y. et al. Precise synthesis of dual atom sites for electrocatalysis. Nano Res. 17, 9397–9427 (2024).

-

Gan, T. & Wang, D. Atomically dispersed materials: ideal catalysts in atomic era. Nano Res. 17, 18–38 (2023).

-

Wu, X. et al. Tuning the d-band center of Co3O4 via octahedral and tetrahedral codoping for oxygen evolution reaction. ACS Catal. 14, 5888–5897 (2024).

-

Rehr, J. J., Kas, J. J., Vila, F. D., Prange, M. P. & Jorissen, K. Parameter-free calculations of X-ray spectra with FEFF9. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 12, 5503–5513 (2010).

-

Duan, J. et al. Selective conversion of polyethylene wastes to methylated aromatics through cascade catalysis. EES Catal. 1, 529–538 (2023).

-

Genuino, H. C. et al. An improved catalytic pyrolysis concept for renewable aromatics from biomass involving a recycling strategy for co-produced polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Green Chem. 21, 3802–3806 (2019).

-

Zeng, L. et al. Recycling valuable alkylbenzenes from polystyrene through methanol-assisted depolymerization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 63, e202404952 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFA1506801 to D.W.) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52376195 to J.W. and 22171157 to D.W.). We gratefully acknowledge the 1W1B beamline of the Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility (BSRF) and BL14W1 beamlines at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF) for providing beam time. We also thank C. Guo at the Analysis Center, Department of Chemistry, Tsinghua University, for assistance with catalyst structure characterization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: J.J. and D.W. Supervision: J.J. and D.W. Methodology: J.W., Z. Zhang, Y.Z., W.L. and D.L. Investigation: Z. Zhuang, J.W., T.H. and S.W. Theoretical calculation: Z. Zhang, D.L. and S.W. Morphology characterization: L.D. and Z. Zhang. Writing (original draft): J.W. and Z. Zhang. Writing (review and editing): D.W. and J.J.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Nanotechnology thanks Guoliang Liu and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–47, Supplementary Notes and Tables 1–22.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, J., Zhang, Z., Zhang, Y. et al. Breaking the yield–selectivity trade-off in polystyrene waste valorization via tandem depolymerization and hydrogenolysis.

Nat. Nanotechnol. (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-025-02069-x

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Version of record:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-025-02069-x