Frontier psychology

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/physiology/rss

Source Author

1 Exercise reshapes hepatic NAD+ metabolism

Exercise serves as more than a means of expending calories; it represents a systemic physiological stimulus (Vargas-Ortiz et al., 2019). Across modalities-including high-intensity aerobic exercise, interval training, and resistance exercise-the hepatic NAD+/NADH ratio increases, forming the biochemical entry point for Sirtuin activation (Imai and Yoshino, 2013). During exercise, cellular energy depletion signals activate AMPK, which subsequently enhances NAD+ biosynthesis through the NAMPT pathway. This establishes the AMPK–SIRT1–PGC-1α signaling axis, a pathway that propagates its effects across nuclear, mitochondrial, and epigenetic regulatory layers (Ruderman et al., 2010; Su et al., 2024). Although most mechanistic insights into the hepatic NAD+–Sirtuin axis derive from rodent models, human exercise studies also support a link between training, NAD+ salvage, and Sirtuin activation. Endurance and resistance training increase NAMPT expression and NAD+ salvage capacity in human skeletal muscle, alongside higher SIRT1 and SIRT3 activity, suggesting that similar systemic signals may impinge on the liver during chronic exercise (Brandauer et al., 2013; Costford et al., 2010; Wasserfurth et al., 2021).

Within this framework, SIRT1, SIRT3, and SIRT6 operate as a coordinated three-tier module of the exercise response (Kanwal et al., 2019; Vargas-Ortiz et al., 2019). Through their sequential activation, exercise promotes a cascade that ultimately contributes to the attenuation of fatty liver pathology (Vargas-Ortiz et al., 2019).

This tiered organization is reflected not only in their activation patterns but also in their distinct functional roles across nuclear, mitochondrial, and epigenetic layers. At the nuclear level, SIRT1 modulates the AMPK–PGC-1α signaling axis to regulate transcription, suppress lipogenesis, and enhance β-oxidation (Anggreini et al., 2022; Cantó and Auwerx, 2009; Wu et al., 2022). At the mitochondrial level, SIRT3 enhances fatty acid oxidation and mitigates reactive oxygen species production through the deacetylation of key metabolic enzymes (Ansari et al., 2017; Bell and Guarente, 2011; Cheng et al., 2016; Trinh et al., 2024; Wu et al., 2022). At the epigenetic level, SIRT6 contributes to hepatic metabolic remodeling by repressing lipogenic transcription factors such as SREBP1c and ChREBP through histone deacetylation (Wu et al., 2022; Zhu et al., 2021). To provide a conceptual overview of how exercise-driven changes in NAD+ metabolism reorganize the hepatic Sirtuin network across nuclear, mitochondrial, and epigenetic layers, this framework is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Integrated conceptual framework of exercise-induced hepatic adaptation mediated by the Sirtuin network (A) Exercise acts as a systemic physiological stimulus that enhances hepatic NAD+ biosynthesis, leading to activation of the Sirtuin network and subsequent hepatic adaptation. The NAD+ molecular structure shown in this panel is adapted from Wikimedia Commons and is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution–ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-SA 4.0). (B) Within this network, SIRT1, SIRT3, and SIRT6 form a central functional core driving primary metabolic remodeling, while SIRT2, SIRT4, SIRT5, and SIRT7 function as modulators that fine-tune, stabilize, and protect the adaptive response. (C) Layer-specific actions of the Sirtuin network are illustrated across nuclear (SIRT1-mediated transcriptional regulation), mitochondrial (SIRT3/5-mediated enhancement of fatty acid oxidation and redox control), and epigenetic (SIRT6-mediated histone deacetylation and repression of lipogenic gene programs) levels, collectively contributing to exercise-induced hepatic remodeling.

2 Why does exercise research focus almost exclusively on SIRT1, SIRT3, and SIRT6?

The dominance of these three Sirtuins in exercise physiology literature does not stem solely from their presumed biological centrality. Rather, they are studied because their experimental behavior is clear, reproducible, and technically tractable (Vargas-Ortiz et al., 2019).

SIRT1 responds rapidly to both endurance exercise and high-intensity interval training, owing to its tight coupling with the AMPK–PGC-1α axis (Cantó and Auwerx, 2009; Imai and Yoshino, 2013; Ruderman et al., 2010). SIRT3 reacts almost immediately after exercise, as it is directly involved in mitochondrial biogenesis and reactive oxygen species regulation (Ansari et al., 2017; Cheng et al., 2016). Meanwhile, SIRT6 becomes more prominent during prolonged training, where its epigenetic effects help explain forms of metabolic “memory” (Kuang et al., 2018; Mostoslavsky et al., 2006).

Because these molecules yield consistent and interpretable results, attention-and consequently funding and publications-has accumulated around them. In other words, research has gravitated toward the Sirtuins that generate visible and stable outcomes (Pacifici et al., 2019).

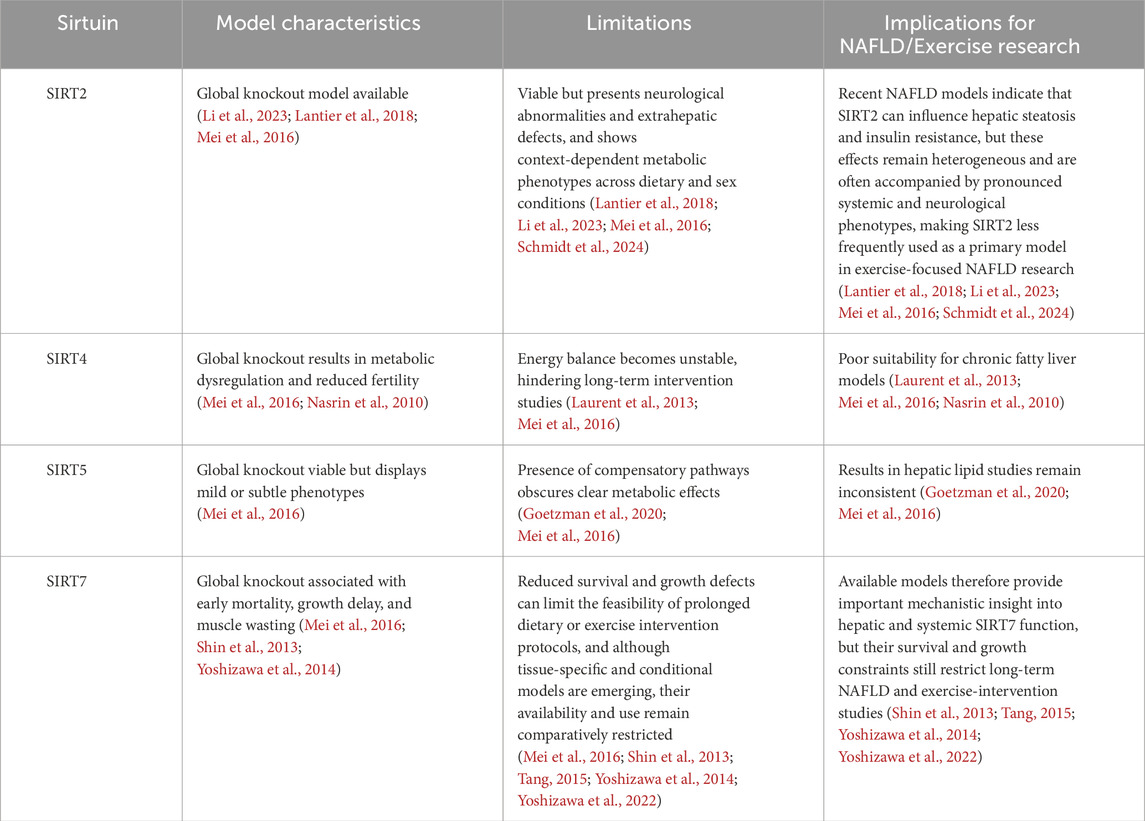

Technical limitations have further reinforced this bias. Among the seven Sirtuin isoforms, viable and well-characterized genetically modified mouse lines exist primarily for SIRT1, SIRT3, and SIRT6. These models remain compatible with whole-body and liver-specific deletion strategies and display clear hepatic metabolic phenotypes under exercise and dietary intervention (Cheng et al., 2016; Kuang et al., 2018; Mostoslavsky et al., 2006). In contrast, SIRT2 and SIRT5 knockout mice show subtle or inconsistent liver phenotypes, while SIRT4 and SIRT7 deletions are associated with reduced viability, growth impairments, or reproductive defects-conditions that hinder long-term exercise-based protocols (Wu et al., 2022; Yoshizawa et al., 2014).

Thus, the current research landscape has been shaped less by the inherent functional importance of only three Sirtuins and more by the practical reality that only a subset is experimentally workable. The field, by necessity, has evolved around what can be studied rather than all that may be biologically relevant (Vargas-Ortiz et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2022).

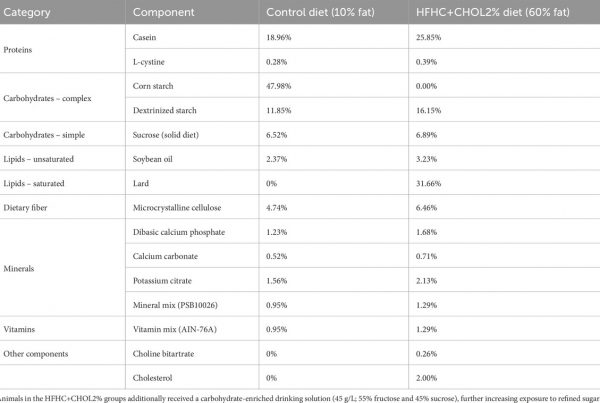

This research imbalance aligns with differences in experimental tractability across Sirtuin isoforms. As shown in Tables 1, 2, the availability and robustness of genetic models have favored SIRT1, SIRT3, and SIRT6, whereas significant limitations remain for SIRT2, SIRT4, SIRT5, and SIRT7.

3 Exercise also influences SIRT2, SIRT4, SIRT5, and SIRT7

Recent findings increasingly suggest that exercise does not selectively activate only SIRT1, SIRT3, and SIRT6, but also induces measurable-though often subtler-changes in the remaining Sirtuin isoforms (Wu et al., 2022).

SIRT2 expression tends to rise alongside reductions in inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α following exercise. This shift is linked to dampened hepatic macrophage activation and improved insulin sensitivity, positioning SIRT2 as a mediator of the exercise-associated anti-inflammatory response. Notably, direct exercise intervention studies using SIRT2-deficient models remain scarce, and current interpretations are largely inferred from metabolic and inflammatory phenotypes rather than confirmed exercise-specific experiments (Lantier et al., 2018). Recent diet-induced NAFLD models further suggest that SIRT2 deficiency can aggravate hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance, although these effects appear to depend on dietary context, sex, and gut microbiota composition (Li et al., 2023; Schmidt et al., 2024).

SIRT4 appears to function differently. By suppressing mitochondrial enzyme activity, it prevents excessive oxidative metabolism during exercise, thereby acting as a safeguard against metabolic overuse and contributing to cellular protection (Laurent et al., 2013; Nasrin et al., 2010).

Although direct evidence linking SIRT5 activity to exercise-induced mitochondrial adaptations in the liver remains limited, SIRT5-mediated desuccinylation has been shown to regulate mitochondrial enzyme efficiency and oxidative stress responses in metabolic tissues. These mechanisms may complement the well-established role of SIRT3 during exercise-induced mitochondrial remodeling, suggesting a potential cooperative relationship under conditions of increased energetic demand (Goetzman et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2022).

SIRT7 responds to exercise-induced translational demand. It contributes to relief of ER stress and supports ribosomal protein expression stability during prolonged adaptation, implying a role in maintaining cellular resilience when exercise becomes a chronic physiological load (Shin et al., 2013; Yoshizawa et al., 2014).

Viewed collectively, if SIRT1, SIRT3, and SIRT6 form the core pathway that generates the metabolic benefits of exercise, then SIRT2, SIRT4, SIRT5, and SIRT7 can be viewed as a complementary regulatory layer-one that fine-tunes, stabilizes, and protects the metabolic remodeling triggered by physical activity (Zeng and Chen, 2022).

4 Beyond the core SIRT1–SIRT3–SIRT6 triad: a post-triadic view of exercise physiology

The current framework in exercise physiology may need to move beyond the question of which Sirtuin becomes activated. A more relevant direction is to examine how the entire Sirtuin network is reorganized in response to exercise intensity, duration, and nutritional context. In this shift, the network-level behavior-not a single molecular response-becomes the central inquiry (Vargas-Ortiz et al., 2019).

Potential directions for future investigation include: 1) Applying single-cell transcriptomic approaches to identify cell-type–specific shifts in hepatic Sirtuin expression following exercise; 2) Using NAD+ flux tracing to define how interactions between SIRT1 and SIRT3 differ across exercise intensities; 3) Exploring diet–exercise combination models to clarify the stress-buffering roles of SIRT4 and SIRT5 (Wasserfurth et al., 2021); 4) Studies following these trajectories would allow exercise physiology to be interpreted not as a series of isolated protein responses but as a dynamic reconfiguration of metabolic circuitry (Han et al., 2019; Schmidt et al., 2024; Yoshizawa et al., 2022).

In addition, emerging questions remain regarding the dynamic regulation of epigenetic modifications beyond SIRT6, including whether other Sirtuin isoforms contribute to the establishment of metabolic memory following repeated exercise exposure. An equally intriguing but largely unexplored area concerns potential transgenerational effects, whereby exercise-induced reorganization of the hepatic Sirtuin network in parents may influence metabolic programming in offspring. This network-based view is consistent with broader systems-level analyses proposing that Sirtuins function as an interconnected metabolic control layer, coordinating energy homeostasis across multiple tissues rather than acting as isolated regulators (Chalkiadaki and Guarente, 2012; Houtkooper et al., 2012; Maissan et al., 2021).

5 Conclusion

Exercise reconfigures hepatic energy metabolism and can reverse fatty liver pathology, with SIRT1, SIRT3, and SIRT6 at the center of this response. Yet the physiological impact of exercise extends far beyond energy expenditure. Throughout this adaptive process, SIRT2, SIRT4, SIRT5, and SIRT7 modulate stress signaling, maintain protein quality control, and support cellular recovery-functions that help sustain long-term hepatic homeostasis.

Viewed in this way, exercise initiates metabolic remodeling through the SIRT1–SIRT3–SIRT6 axis and completes that adaptation through the regulatory functions of SIRT2, SIRT4, SIRT5, and SIRT7. If past work has focused primarily on the “engine” that drives metabolic output, future exercise physiology must also consider the braking and cooling systems-the mechanisms that stabilize and regulate the response. Only then does the full molecular rationale for how exercise restores hepatic function become clear.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JK: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for this research or its publication.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges that no assistance was received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. The author acknowledges the use of generative artificial intelligence tools for limited language-related assistance only, specifically for grammar checking and correction of typographical errors. All scientific content, interpretations, and conclusions were conceived, written, and verified entirely by the author.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ansari A., Rahman M. S., Subroto K. S., Saha D., Saikot F. K., Deep A., et al. (2017). Function of the SIRT3 mitochondrial deacetylase in cellular physiology, cancer, and neurodegenerative disease. Aging Cell 16, 4–16. doi:10.1111/acel.12538

Barroso E., Rodríguez-Rodríguez R., Zarei M., Pizarro-Degado J., Planavila A., Palomer X., et al. (2020). SIRT3 deficiency exacerbates fatty liver by attenuating the HIF1α-LIPIN1 pathway and increasing CD36 through Nrf2. Cell Commun. Signal 18, 147. doi:10.1186/s12964-020-00640-8

Brandauer J., Vienberg S. G., Andersen M. A., Ringholm S., Risis S., Larsen P. S., et al. (2013). AMP-Activated protein kinase regulates nicotinamide phosphoribosyl transferase expression in skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 591 (20), 5207–5220. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2013.259515

Cantó C., Auwerx J. (2009). PGC-1alpha, SIRT1 and AMPK, an energy sensing network that controls energy expenditure. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 20 (2), 98–105. doi:10.1097/MOL.0b013e3283280da4

Cheng A., Yang Y., Zhou Y., Maharana C., Lu D., Peng W., et al. (2016). Mitochondrial SIRT3 mediates adaptive responses of neurons to exercise and metabolic and excitatory challenges. Cell Metab. 23 (1), 128–142. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2015.10.013

Costford S. R., Bajpeyi S., Pasarica M., Albarado D. C., Thomas S. C., Xie H., et al. (2010). Skeletal muscle NAMPT is induced by exercise in humans. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 298 (1), E117–E126. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00318.2009

Gibril B. A. A., Xiong X., Chai X., Xu Q., Gong J., Xu J. (2024). Unlocking the nexus of sirtuins: a comprehensive review of their role in skeletal muscle metabolism, development, and disorders. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 20 (8), 3219–3235. doi:10.7150/ijbs.96885

Goetzman E. S., Bharathi S. S., Zhang Y., Zhao X.-J., Dobrowolski S. F., Peasley K., et al. (2020). Impaired mitochondrial medium-chain fatty acid oxidation drives periportal macrovesicular steatosis in sirtuin-5 knockout mice. Sci. Rep. 10, 18367. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-75615-3

Han Y., Zhou S., Coetzee S., Chen A. (2019). SIRT4 and its roles in energy and redox metabolism in health, disease and during exercise. Front. Physiol. 10, 1006. doi:10.3389/fphys.2019.01006

Imai S., Yoshino J. (2013). The importance of NAMPT/NAD/SIRT1 in the systemic regulation of metabolism and aging. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 15 (3), 202–210. doi:10.1111/dom.12171

Kanwal A., Pillai V. B., Samant S., Gupta M., Gupta M. P. (2019). The nuclear and mitochondrial sirtuins, Sirt6 and Sirt3, regulate each other’s activity and protect the heart from developing obesity-mediated diabetic cardiomyopathy. FASEB J. 33 (10), 10872–10888. doi:10.1096/fj.201900767R

Kendrick A. A., Choudhury M., Rahman S. M., McCurdy C. E., Friederich M., Van Hove J. L., et al. (2011). Fatty liver is associated with reduced SIRT3 activity and mitochondrial protein hyperacetylation. Biochem. J. 433 (3), 505–514. doi:10.1042/BJ20100791

Lantier L., Williams A. S., Hughey C. C., Bracy D. P., James F. D., Ansari M. A., et al. (2018). SIRT2 knockout exacerbates insulin resistance in high fat-fed mice. PLoS One 13 (12), e0208634. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0208634

Laurent G., German N. J., Saha A. K., de Boer V. C. J., Davies M., Koves T. R., et al. (2013). SIRT4 coordinates the balance between lipid synthesis and catabolism by repressing malonyl-CoA decarboxylase. Mol. Cell 50 (5), 686–698. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2013.05.012

Li X., Du Y., Xue C., Kang X., Sun C., Peng H., et al. (2023). SIRT2 deficiency aggravates diet-induced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease through modulating gut microbiota and metabolites. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 8970. doi:10.3390/ijms24108970

Maissan P., Mooij E. J., Barberis M. (2021). Sirtuins-mediated system-level regulation of mammalian tissues at the interface between metabolism and cell cycle: a systematic review. Biology 10 (3), 194. doi:10.3390/biology10030194

Mostoslavsky R., Chua K. F., Lombard D. B., Pang W. W., Fischer M. R., Gellon L., et al. (2006). Genomic instability and aging-like phenotype in the absence of Mammalian SIRT6. Cell 124 (2), 315–329. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.044

Nasrin N., Wu X., Fortier E., Feng Y., Bare O. C., Chen S., et al. (2010). SIRT4 regulates fatty acid oxidation and mitochondrial gene expression in liver and muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 285 (42), 31995–32002. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.124164

Pacifici F., Di Cola D., Pastore D., Abete P., Guadagni F., Donadel G., et al. (2019). Proposed tandem effect of physical activity and sirtuin 1 and 3 activation in regulating glucose homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20 (19), 4748. doi:10.3390/ijms20194748

Ruderman N. B., Xu X. J., Nelson L., Cacicedo J. M., Saha A. K., Lan F., et al. (2010). AMPK and SIRT1: a long-standing partnership? Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 298, E751–E760. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00745.2009

Schmidt A. V., Bharathi S. S., Solo K. J., Bons J., Rose J. P., Schilling B., et al. (2024). Sirt2 regulates liver metabolism in a sex-specific manner. Biomolecules 14 (9), 1160. doi:10.3390/biom14091160

Shin J., He M., Liu Y., Paredes S., Villanova L., Brown K., et al. (2013). SIRT7 represses myc activity to suppress ER stress and prevent fatty liver disease. Cell Rep. 5 (3), 654–665. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2013.10.007

Su M., Qiu F., Li Y., Che T., Li N., Zhang S. (2024). Mechanisms of the NAD+ salvage pathway in enhancing skeletal muscle function. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 12, 1464815. doi:10.3389/fcell.2024.1464815

Vargas-Ortiz K., Pérez-Vázquez V., Macías-Cervantes M. H. (2019). Exercise and sirtuins: a way to mitochondrial health in skeletal muscle. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20 (11), 2717. doi:10.3390/ijms20112717

Wang R. H., Kim H. S., Xiao C., Xu X., Gavrilova O., Deng C. X. (2011). Hepatic Sirt1 deficiency in mice impairs mTorc2/Akt signaling and results in hyperglycemia, oxidative damage, and insulin resistance. J. Clin. Invest 121 (11), 4477–4490. doi:10.1172/JCI46243

Wasserfurth P., Nebl J., Rühling M. R., Shammas H., Bednarczyk J., Koehler K., et al. (2021). Impact of dietary modifications on plasma sirtuins 1, 3 and 5 in older overweight individuals undergoing 12-weeks of circuit training. Nutrients 13 (11), 3824. doi:10.3390/nu13113824

Wu Q.-J., Zhang T.-N., Chen H.-H., Yu X.-F., Lv J.-L., Liu Y.-Y., et al. (2022). The sirtuin family in health and disease. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 7, 402. doi:10.1038/s41392-022-01257-8

Xiao C., Wang R. H., Lahusen T. J., Park O., Bertola A., Maruyama T., et al. (2012). Progression of chronic liver inflammation and fibrosis driven by activation of c-JUN signaling in Sirt6 mutant mice. J. Biol. Chem. 287 (50), 41903–41913. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.415182

Xu F., Gao Z., Zhang J., Rivera C. A., Yin J., Weng J., et al. (2010). Lack of SIRT1 (Mammalian sirtuin 1) activity leads to liver steatosis in the SIRT1+/− mice: a role of lipid mobilization and inflammation. Endocrinology 151 (6), 2504–2514. doi:10.1210/en.2009-1013

Yoshizawa T., Karim M. F., Sato Y., Senokuchi T., Miyata K., Fukuda T., et al. (2014). SIRT7 controls hepatic lipid metabolism by regulating the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway. Cell Metab. 19 (4), 712–721. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2014.03.006

Yoshizawa T., Sato Y., Sobuz S. U., Mizumoto T., Tsuyama T., Karim M. F., et al. (2022). SIRT7 suppresses energy expenditure and thermogenesis by regulating brown adipose tissue functions in mice. Nat. Commun. 13, 7439. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-35219-z

Zhong X., Huang M., Kim H. G., Zhang Y., Chowdhury K., Cai W., et al. (2020). SIRT6 protects against liver fibrosis by deacetylation and suppression of SMAD3 in hepatic stellate cells. Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 10 (2), 341–364. doi:10.1016/j.jcmgh.2020.04.005

Zhu C., Huang M., Kim H. G., Chowdhury K., Gao J., Liu S., et al. (2021). SIRT6 controls hepatic lipogenesis by suppressing LXR, ChREBP, and SREBP1. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 1867 (12), 166249. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2021.166249